Integrated Illumination

The choices one has in microscope illumination are often, of late, made by the microscope manufacturer. That choice is not always the one that the user would make for themselves, or even the best for general use. In general one might say that with integrated illumination, whatever the quality, age, or price of the microscope, one can rely on prompt success when it comes to simply obtaining an image. The perfectness of that image may range from excellent to abyssal, but something will certainly be seen at the eyepiece.

Today, if one is possessed of a microscope with integrated illumination little need be done for acceptable operation. A microscope equipped with a mirror is as easy for general, but more complex for critical work, when compared to a stand with integrated illumination. The mirror microscope is next to impossible to use at its full ability without a measure of effort and understanding of some of the methods of illumination for transmitted light microscopy. Let us begin by looking first towards a number of microscopes equipped with integrated illumination of various sorts and speak to the merits and abilities of each.

Köhler Illumination with the BalPlan

This model of the Bausch & Lomb Balplan uses a halogen lamp mounted in the base to illuminate a ground glass Plano-convex lens secured in the base. From there, a beam is sent through an iris diaphragm and fixed focus lens towards a right angle mirror which sets the light vertically through a second lens. The coherent light which emanates from this lens is then passed through the microscopes rack and pinion 1.25N.A. aplanatic condenser. The condenser is equipped with an auxiliary lens which may be swung into place to expand the pencil of light and provide a large enough light source for use with a low power finder objective.

This model of the Bausch & Lomb Balplan uses a halogen lamp mounted in the base to illuminate a ground glass Plano-convex lens secured in the base. From there, a beam is sent through an iris diaphragm and fixed focus lens towards a right angle mirror which sets the light vertically through a second lens. The coherent light which emanates from this lens is then passed through the microscopes rack and pinion 1.25N.A. aplanatic condenser. The condenser is equipped with an auxiliary lens which may be swung into place to expand the pencil of light and provide a large enough light source for use with a low power finder objective.

With an object in place (and in focus) it is the work of a moment to obtain a focused image of the iris of the illuminator using the condenser, and adjust the iris of the condenser to so that the numerical aperture of the condenser matches that of the objective for true Köhler illumination. The method of August Köhler to provide a field of light perfectly uniform and out of focus, while retaining all the characteristics required for maximum resolution are today recognized and accepted as optimum for advanced work. Köhler illumination puts a focused image of the light source (the filliament of the lamp or grain of a ground glass screen) at the iris diaphragm opening of the substage condenser and again at the back focal plane of the objective. A bright evenly lit field is then formed at the iris diaphragm opening of the illuminator and in the image plane of the focused microscope slide.

In the photograph the illuminators iris diaphragm has been stopped down well beyond what would be used in practice to better show the in focus diaphragm simultaneous with the image plane of the specimen. Note that despite the light source being a ground glass there is no visible grain in the photomicrograph.

Critical Illumination with the AO Fifty

This American Optical Fifty series microscope makes use of an uncomplicated 15watt (medium base) incandescent bulb as the light source. Mounted in an adjustable housing in the microscopes base the light of the bulb is sent first through a blue filter. Immediately above the filter is mounted a single short focus Plano-convex lens with a ground glass flat surface. This arrangement makes up the integrated illuminator common to microscopes of the Fifty, Sixty, One-Fifty, and One-Sixty series. Above the field lens of the illuminator is a 1.25N.A. Abbe condenser on rack and pinion adjustment.

This American Optical Fifty series microscope makes use of an uncomplicated 15watt (medium base) incandescent bulb as the light source. Mounted in an adjustable housing in the microscopes base the light of the bulb is sent first through a blue filter. Immediately above the filter is mounted a single short focus Plano-convex lens with a ground glass flat surface. This arrangement makes up the integrated illuminator common to microscopes of the Fifty, Sixty, One-Fifty, and One-Sixty series. Above the field lens of the illuminator is a 1.25N.A. Abbe condenser on rack and pinion adjustment.

With this setup Köhler illumination is not possible. Instead a less perfect but far less mechanically demanding type of illumination known as critical illumination is possible. Prior to the modern∗ acceptance of Köhler illumination as the gold standard it was practice to work with a large light source and less complex illumination apparatus. Rather than a focused image of the light source, a brightly lit field is formed at the opening of the substage iris diaphragm and the back focal plane of the objective†. Unfortunately, this results in a focused image of the light source (and all its attendant grain or irregularities) being formed in the image plane of the specimen. The worker is then apt to throw the substage condenser slightly out of focus so as to avoid the distracting image of the filament when not using a sufficiently large homogeneous light source.

Not that in the upper photomicrograph there is evidence of dust on the ground glass illuminator, as shown by dark areas indicated by the pointer. In the lower photomicrograph the substage condenser has been thrown slightly out of focus to prevent grain and dust from appearing in the image plane of the specimen. In general use one may chose to rack the condenser up or down if the grain of the illuminator is found distracting, there is however a slight increase in spherical aberration and decrease in resolution.

Add-on Integrated Illumination

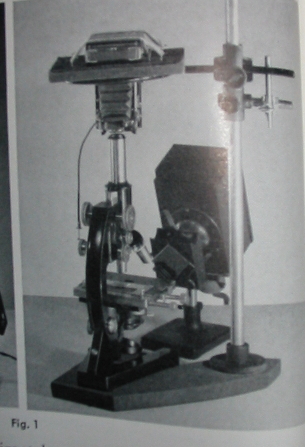

Largely as a response to the need for simplicity and convenience when introducing microscopy to students, a large number of manufacturers began to sell small self-contained light sources in the mid-twentieth century. These simple lamps could be used in the conventional way with a mirror bearing microscope by sitting the lamp upon the table, or by mounting it directly to the base of the microscope. The Bausch & Lomb lamp shown here was available with two different mounting brackets; one which made use of the mirrors mount, and that pictured which would be fit over the removable substage iris diaphragm before it was screwed back into the base of the substage condenser.

Largely as a response to the need for simplicity and convenience when introducing microscopy to students, a large number of manufacturers began to sell small self-contained light sources in the mid-twentieth century. These simple lamps could be used in the conventional way with a mirror bearing microscope by sitting the lamp upon the table, or by mounting it directly to the base of the microscope. The Bausch & Lomb lamp shown here was available with two different mounting brackets; one which made use of the mirrors mount, and that pictured which would be fit over the removable substage iris diaphragm before it was screwed back into the base of the substage condenser.

This illuminator consists of a small 15watt (medium base) incandescent bulb in a switched, sturdy, Bakelite shell. Over the bulb is mounted a blue glass filter with one ground glass surface, followed by a Plano-convex lens. The exposed convex surface of the lens is ground as well. Depending on the arrangement in which the illuminator is used, one can work with critical illumination or not, but again Köhler illumination is not possible‡.

Such lamps are chiefly recommended by their simplicity, durability, and availability at low cost. Less often mentioned is the versatility of such lamps. Any illuminator of this sort§ may be arranged to provide ample light in most circumstances a beginning microscopist is likely to encounter. It may be used with or without a substage condenser, or even without the mirror; as it may be set on the table between the foot of the microscope with the light projecting upwards through the stage. If such a light source is to be used it should be considered a component of the microscope, and kept with it at all times.

In the upper photomicrograph the lamp was placed on its back below the substage. Although the illumination is not critical the central portion of the field is even lit and free of grain. In the lower photomicrograph the lamp was positioned ten inches from vertical axis of the microscope and its light reflected by the plane mirror. With the surface of the ground glass focused critical illumination resolves the center of the field of view with slightly less spherical abbaration, although grain is once more introduced into the image and it is evident that this author did not take time to properly center the lamp.

Notes:

∗Well into the twentieth century arguments continued to be raised as to the technical or practical superiority of the various methods of specimen illumination. One may at first wonder at the controversy but it seems to have largely resulted from the need for more specialized light sources with Köhler illumination and the practicality of critical illumination when used with any large (flame or cloud for example) light source. The past popularity of point light sources is a product of the growing pains of the adoption of Köhler illumination as it was generally felt that a bright point of light provided more capacity for filtering without diminishing intensity.

†Technically, in critical illumination that brightly lit filed is formed just before the back focal plane of the objective and moves closer towards it as the power of the objective is increased.

‡Obviously with the lamp mounted directly to the substage condenser one can not bring the ground glass surface into focus in the specimen image plane as is required for critical illumination. Working with the lamp on the work table, or with the lamp mounted to the mirror bracket it may be brought into focus with the substage condenser if it is in range of the primary focus. I am uncertain as to why B&L would grind the convex surface of the lens, but I suspect it was motivated more by the desire to make the device less open to damage by unskilled hands (there are no exposed polished lenses to worry about) than by optical concerns.

§All of the major manufacturing houses put out similar lamps with differing arrangements as to bulb and glass. A popular American Optical model was equipped with a blue filter and swing out ground glass or bullseye lens, providing a limited means of controlling the intensity of the light. Modern LED or incandescent lamp housings are available that will mount in place of the double sided mirror of most vintage stands, one need only verify that the mounting is compatible.

If things seem complicated don’t wait on the availability of fancy equipment, great work has been done with desk lamps and white clouds. Next time we’ll look to external illuminators. -K