In a sense it’s all just assisted freehand, but I think the meaning is clear. -K

Yesterday efforts were made at getting something on paper and learning a bit on setting up properly. Regrettably those efforts will have accomplished very little of a immediately practical sort. The images produced might be used to visually identify a slide at a glance if its label has fallen off, but that is assuming there are no similar slides on hand. My little sketch could verify that it is of a letter “e” but one would be hard pressed in putting it definitely to a particular unlabeled slide of a letter “e”. Because there was no assistive device that would help with sizing and dimension, we end up only with a general rather than an accurate depiction; one couldn’t use the sketch to measure the size of the letter.

Fortunately, the technique used previously can be rendered very practical by the addition of a simple object that may be purchased for from ten to fifty dollars, or made at home for a good deal less. This device can be used for any number of very usefull tasks from micrography to counting, measuring, or locating. One can use it on essentially any microscope at any magnification and it will last a lifetime. This miraculous device? The humble graticule also erroneously designated the reticle or reticule.

A graticule, the name of which comes from the Latin for gridiron, is nothing more than an optical device on which a ruling of small squares has been marked. This is technically the only accurate description for a graticule as markings composed of either various lines or any grid which is not broken up into even shapes would be a reticule; a micrometer or sighting ocular is a reticule, while a simple counting ocular is a graticule (excluding of course the complex rulings of Neubauer which would be in places reticule or graticule). In practice few people make any distinction between the terms and one is likely to find suitable graticules under various names.

The use of a graticule is quite simple and requires only an eyepiece that contains a diaphragm located at the point in which a real image is formed. In practice this means a negative ocular of the Huygenian type with a field stop between the object lens and the eye lens. At the optical plane of the field stop a real magnified image of the object is formed, which may be observed by placing a circle of tissue paper or frosted glass thereupon. When the graticule (or anything for that matter) is positioned at a point where a real image is formed it will be seen conjugate with the virtual image one observes when looking into the eyelens of the ocular. For more detail concerning real and virtual images one can consult the section on Object-Image Math in Douglas B. Murphy’s excellent book Fundamentals of Light Microscopy and Electronic Imaging.

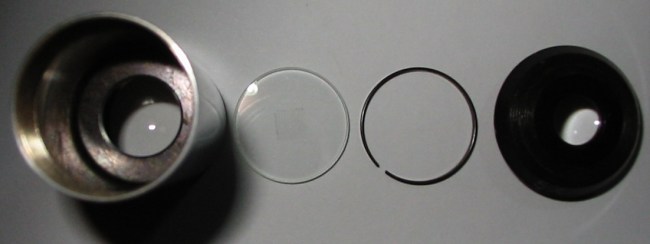

So, assuming one posses a graticule either purchased or home made and a Huygenian ocular with removable optics, one may fit the graticule to the ocular. Begin in a scrupulously clean and dust free area, as nothing is quite so infuriating as introducing dust to the inside of an ocular, and unscrew the eyelens. With the eyelens removed insert the graticule which should fit just within the tube without force or slop. For standard oculars by Bausch & Lomb and most American makers a graticule with a 21mm diameter is best. In some cases manufacturers provide split rings (as pictured) which will hold the graticule in place so that it will not rattle about even if the ocular be roughly treated. If one is had and the graticule is to be left always in a particular ocular place the split ring before screwing back into position the eyelens of the ocular.

With the majority of graticules the lines are ruled upon one surface or the other and each orientation should be tried. If the rulings are more clearly in focus with the eyelens screwed fully home then that orientation should be selected before one settles for having a loosely fitted eyelens. With the graticule in place in the ocular one should focus a slide upon the stage of the microscope and observing it with the ocular find both the rulings and the specimen sharply defined. If the rulings will not come to focus conjugate with the specimen, the eyelens must be screwed down or up until they are. The eyelens and orientation of the graticule should be manipulated until the rulings are truly conjugate with the image of the specimen. Which is to say they should be neither more or less sharply defined and appear as if on the same level as the object although overlayed.

For drawing with a graticule one would do best to use an ocular of low power and obtain higher magnification with the objective only. The reason for this is well explained by the equations in the above mentioned book but, suffice to say that the area covered by each square of the graticule at a given magnification will be less when that magnification is obtained with a low powered ocular. With the graticule in place one need only use a drawing surface ruled into squares to transfer by hand the view seen through the ocular to paper in the method described yesterday. The rulings will assist in both positioning and consistently representing the size of specimens sketched.

In the above photo one might notice that the graticule pictured has rulings in only the very central portion. At first it might seem as if the ruled area being less than that of the oculars diaphragm would be a great hindrance as the entire field of view would not appear ruled. The reason for using this particular graticule will be obvious when it is noted that it is not used with flat-field objectives. By limiting the area covered by the rulings to the central third of the field of view one insures that spherical aberration of any significance is not depicted in ones micrographs. Images in which optical defects are faithfully represented are of as dubious value as live blood examinations where quacks point to specks of dust or dirt as proof of one malady or another…

Now then, if one knows the spacing of the rule on both the graticule and drawing surface, together with the magnification employed, measurements of a sort may be taken on the drawing using no more specialized apparatus than a ruler. This method of measurement is rather less precise than others (tough quite accurate) but requires neither a micrometer object slide or micrometer eyepiece and serves well for work of all but the most critical sort.

With a graticule in place and ruled paper one may produce micrographs of impeccable quality and enormous size (by moving the slide so that the contents of a square are transported across the field). If one is of limited resources or has in the past attempted other apparatus without good results, no better aid to drawing with the microscope can be had than the graticule. Unlike other apparatus to be covered later no special positioning of the microscope is needed and no great effort is required to become adept. An ocular fitted with a graticule may be dropped into position and used at a moments notice, I commend it to any microscopist.